I’m sitting in a crowded restaurant surrounded by chattering diners, whispering waiters and the clatter of dishes . Then in an instant I’m transported to a church service and the sounds of a solemn ceremony. Another flick of the switch and I’m amid the hubbub of an awards show listening to the MC and the people at my table.

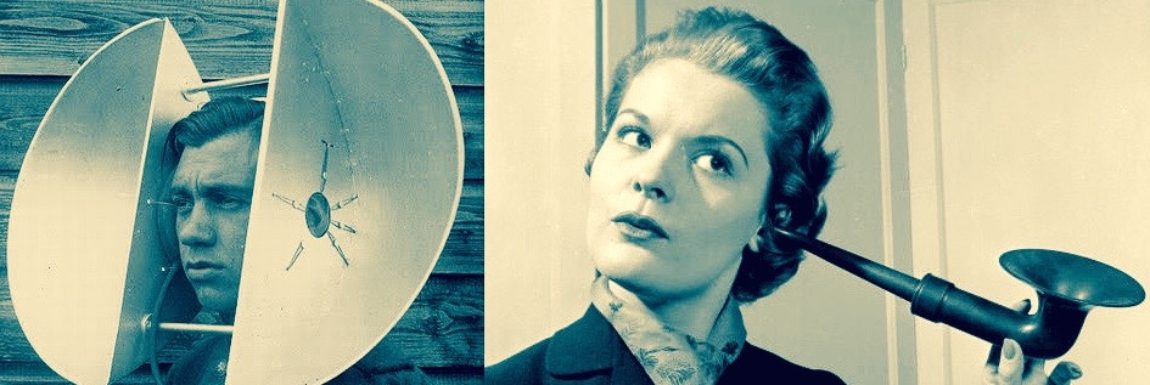

In fact I was in none of those places. Instead I was sitting with my eyes closed in the centre of a spherical loudspeaker array in an anechoic chamber (an echo free, sound absorbing room) at Australia’s National Acoustic Laboratories in Sydney.

I was listening to field recordings made by NAL researchers James Galloway and Jason Heeris. It’s Dolby Surround Sound times a thousand. Even to my failing ears the effect is stunningly immersive.

Their work produces incredibly detailed acoustic images of the real world. It’s processed with sophisticated software and shared with researchers around the world. It can be used to develop and test hearing aid designs for example.

It’s only one of an impressive range of projects underway at the NAL. The NAL is the research division of Australian Hearing which is a government body that traces its roots to military research during WWII when many veterans were exposed to the ear shattering sounds of war. After the war its work took on new urgency when a rubella outbreak left many Australian children with hearing loss.

The NAL is overseen by Director Dr. Brent Edwards, who has a resume that spans 20 years of helping people hear better with companies such as Starkey, GN Resound and Earlens.

Looking ahead, Edwards sees the world of big data converging with AI to produce better hearing aids and change the way hearing loss is diagnosed and treated.

That’s one reason why the NAL is working on projects to connect with people in remote parts of Australia who have hearing loss so that they can become, in effect, their own audiologist able to fit and adjust their hearing aids by themselves.

Another important research project is helping to diagnose and treat hearing loss in very young children. Standard hearing tests are difficult to administer to infants because they don’t yet have the verbal skills to respond to questions about which frequencies they can or cannot hear.

The NAL’s program gets around this issue by using electroencephalography. It’s a common technology that involves using electrodes to record electrical activity in different areas of the brain.

Using EEG researchers can “see” which sounds the child’s brain is, or is not, responding to. That gives them the information they need to proscribe more effective treatments.

NAL also plays a large role in raising Australians’ awareness of hearing loss, how to treat it and how to prevent it. It supports a program called HEARsmart which is designed to reach young people with tips and advice on how to avoid damaging their ears.

As far I can tell, the NAL and Australian Hearing are unique in the world but it’s not just Australians who benefit from their work. As a matter of fact, if you wear hearing aids there’s a good chance the audiologist used a prescriptive fitting formula developed at the NAL.

Based on what I’ve learned, the NAL will continue to have a positive impact on the lives of people with hearing loss wherever they are.